BUCHAREST — This summer, after the police arrived at the handsome villa of the former Romanian prime minister Adrian Nastase to arrest him on corruption charges, he apparently pulled out a revolver and tried to kill himself. Millions of Romanians watched on television as Mr. Nastase, 62, was carried off on a stretcher, a Burberry scarf wrapped around his neck. He survived, and one week later was behind bars. But this is Romania, where everything, it seems, is a matter of dispute.

Anti-corruption advocates hailed Mr. Nastase’s downfall as a seminal moment in the evolution of a young democracy. Others have called his conviction for siphoning $2 million in state funds for his presidential campaign a show trial. Mr. Nastase’s opponents now allege that he faked a suicide attempt in an effort to avoid prison. His son Andrei Nastase, who was at the house at the time, said the accusation was absurd.

Whatever the truth, Adrian Nastase now occupies a cell measuring 4 square meters, or 43 square feet. On his jailhouse blog, he recently recounted how prisoners ate cabbage and potatoes, braved rats and had hot water for two hours twice a week.

Today, analysts here and abroad say the Nastase case has come to reveal as much about Romania’s political polarization and dysfunction as its halting steps toward greater democracy. It comes amid heightened fears in the European Union that its newest and weakest members are not up to the task of rooting out corruption that is a legacy of decades of Communist rule and, indeed, of weak governance before that.

Across Eastern and Central Europe and the Balkans, countries are experiencing a surge of instability that, analysts say, stems almost in equal parts from endemic corruption and the sometimes ham-fisted efforts to combat it in the context of bitter political rivalries.

The European Union, with 27 member nations, is so concerned about creeping lawlessness among its new members that Romania and its neighbor Bulgaria, which both entered in 2007, have not joined the bloc’s passport/visa-free travel area. On Thursday, the European Commission, the executive body of the European Union, said concerns about corruption and fraud in Romania had prompted it to block E.U. development aid, potentially worth billions of euros.

The European Union, with 27 member nations, is so concerned about creeping lawlessness among its new members that Romania and its neighbor Bulgaria, which both entered in 2007, have not joined the bloc’s passport/visa-free travel area. On Thursday, the European Commission, the executive body of the European Union, said concerns about corruption and fraud in Romania had prompted it to block E.U. development aid, potentially worth billions of euros.

In Croatia, which is set to join the European Union next year, former Prime Minister Ivo Sanader has been charged with embezzlement.

Romania, in particular, has struggled to overcome the aftermath of the ruthless, corrupt dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu. Over the past six years, 4,700 people have gone to trial on corruption charges, including 15 ministers and secretaries of state, 23 members of Parliament and more than 500 police officers.

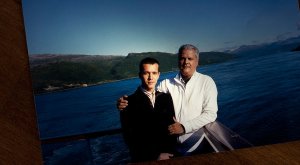

To many, Mr. Nastase, a former member of the Communist elite who was prime minister from 2000 to 2004, is emblematic of a generation of still active politicians who assumed that power and influence could shelter them from the law. Once asked to account for his apparent wealth, he defiantly roared, “Count my eggs!” a Romanian slang word for genitals.

Monica Macovei, a former justice minister who is close to Mr. Nastase’s archrival President Traian Basescu, said that “There are too many people from the Communist era like Nastase who are still in power, and this has polluted the political class.” Read more in The New York Times.

No comments:

Post a Comment