The most slandered and misrepresented historical period of Romanity[1]

The

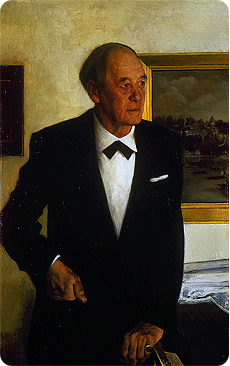

following interview with the great historian and Byzantologist Sir

Steven Runciman can be characterized as the quintessence of his great

work, which is globally renown and recognized. His statements are

momentous and his words mature and wise in meaning, extractions of

thorough and objective life-long study of all expressions of the

'Byzantine' civilization. They truly are blows to the profane mouths

which regurgitate generalizations, smear-talk and insults about anything

relating to this millennium. And the most detestable thing is that the

majority of these unlearned people who follow this trend is that they

are 'ours', being 'Romans (Romioi)'*.

And so, deservingly they receive the brash title of 'Greekling*', while

this Celtic scientist of noble descent sits on the bright firmament of

Hellenophiles.

* a Greek not worthy of their cultural heritage; servile to foreigners and things foreign

The

following viewpoints of Sir Steven Runciman are more relevant in modern

days than at any other time. He warns us so that we can finally wake up

and understand the real reasons that drove us to today's degradation,

to the new state of occupancy of our nation―surely to the worst one so

far, since everything takes place fraudulently and behind the scenes. We

must understand that it is impossible to build our future as a healthy

nation when we have rejected our bright past, at the advice of

opportunists. Let us listen to the people who have demonstrated their

honest love towards our tormented race through their life and morals.

At

the end of the interview the respectable researcher makes reference to

Orthodoxy in relation to other dogmas. We believe it is important to

consider the views as perspectives of a man who is not part of this

sphere. We note that certainly it is not possible to perceive them as

regular Orthodox teachings. Besides, the speaker was not Orthodox.

******

BYZANTIUM AND US

“Sir Steven Runciman: We Need Spiritual Humility”, Nov. 6, 2000,

Εxtract from an interview with Sir Steven Runciman

Εxtract from an interview with Sir Steven Runciman

The

following interview was given by Sir Steven Runciman, in Elseselds,

Scotland, in his ancestral chateau, in October 1994, for ET3, to

journalists Chrysa Arapoglou and Labrini H. Thoma. Because of technical

reasons it never aired on TV. Both journalists consider this interview

as one of the most important in their career since it was one of those

'discussions' that shape you and which you never forget. They believe it

should be made public, at least on the occasion such a sad event, as is

the death of this great friend of the Greek nation. Flash.gr has

published, for the first time, unpublished extracts from this

interview.

Journalist: How does a man feel that has studied the Byzantium for so many years? Are you tired?

It

is hard to answer. My interest never dissipated. When I started

studying Byzantium, there were very few people in this country (i.e.

Great Britain) that were interested, even minutely in Byzantium. I like

to believe that I have created 'interest' in Byzantium. What satisfies

me, especially today, is that now there are several, very good

representatives (i.e. in the study of Byzantium) in Britain. I may say

that I feel like a father towards them. So I am glad that I chose

Byzantium as my main interest.

And was it attractive to you all these years?

And was it attractive to you all these years?

I

believe that if you start studying every event in history thoroughly,

it can become exciting. I find Byzantium especially exciting because it

was a self-sufficient civilization. To study Byzantium, you must study

its art first, study religion, study a whole way of life, which is very

different to today's.

Better or Worse?

Look…

I am not sure that I would like to live in Byzantine times. I wouldn't

like, for example, to grow a beard. Still, in Byzantium they had a way

of life which was better structured. Besides, when you have a strong

religious sense, your life 'is given shape' and is much more

satisfactory than today's, where one does not believe enough in

anything.

So was it a religious state?

It was a civilization in which religion constituted the main way of life.

In all the eleven centuries?

I

think people talk about Byzantium as if it remained the same, a

stagnant civilization during all those centuries. It changed

dramatically from the beginning to its end, even if some basic factors

lasted throughout its entire duration―such as the religious sense. They

may have had disagreements on the various religious matters, but they

were all believers and this feeling was constant. Respect and

appreciation to the arts, as those that please God, those were preserved

as well. And so, despite the fact that fashions changed, the economic

situation changed, the political status quo changed, there was a very

interesting integrity, on the whole.

We

are talking about religion and morals. Byzantium is considered by many a

period of wars, murders, intrigues, 'Byzantinisms' that had nothing to

do with morals.

Many

murders also occurred then, but there is no period in history from

which they are missing. One time I was giving a lecture in the USA, and

in my audience there was the daughter of President Johnson, who was

studying Byzantium. She came to the lecture with two body guards, two

tough men who watched over her. She explained to me that they love

Byzantine history, because it is filled with murders and brings to mind

school lessons (homework). I had the tact not to tell her that up until

then, the percentage of American presidents that had been murdered was

much higher―in relation to the years the US has existed―from the

percentage of murdered Byzantine emperors during the empire. People

continue to murder. Open your eyes!

You have written that in Byzantine civilization there was no death penalty.

Indeed, they did not kill. And the big difference is evident in the initial period. When the Roman Empire turned Christian, one of the most essential changes was to stop gladiatorial games, not throw people to lions anymore, and all those things.

The empire became much more humanitarian. And they always avoided as

much as possible the death penalty. At times, some emperors resorted to

it, but the majority used as a last resort punishment, a method that

today seems hideous to us: some sort of mutilation. But I think that

most people would rather have a hand cut, for example, than be put to

death.

For some time, an open dialogue has been taking part in Greece. There are contemporary Greek intellectuals that claim that Byzantium is not particularly worth studying, since it did not create anything, as it entailed commentators of the scriptures and not intellectuals. In a phrase “it was nothing memorable”.

For some time, an open dialogue has been taking part in Greece. There are contemporary Greek intellectuals that claim that Byzantium is not particularly worth studying, since it did not create anything, as it entailed commentators of the scriptures and not intellectuals. In a phrase “it was nothing memorable”.

I

think that those Greeks are very biased with their Byzantine ancestors.

It was not a society without intellectuals; it's enough to look at the

work and progress of Byzantine medicine. One may dislike religion, but

some of the religious writers like the Cappadocian fathers, and many

others, up to Gregory Palamas, were people of unique spirituality...

Intense intellectualism and spiritual life existed in Byzantium.

Especially, in the late Byzantine years, i.e. The period under the

Palaiologoi. It is especially curious, that at the time when the empire

was shrinking, intellectual thinking was blossoming more than ever.

Others claim there was no art.

Then they must not know anything about art. Byzantine art was one of the greatest art schools worldwide. No ancient Greek would have been able to build St Sophia, this required a very deep technical knowledge. Some, as you know, claim that Byzantine art is static. It was not at all static, but it was one of the most important art schools in the world, which as time passes, it is more appreciated, and the Greek intellectuals who tell you that Byzantium did not create anything are blind.

So the ones that characterize Byzantine art as “simple imitation and copying” are probably mistaken.

Then they must not know anything about art. Byzantine art was one of the greatest art schools worldwide. No ancient Greek would have been able to build St Sophia, this required a very deep technical knowledge. Some, as you know, claim that Byzantine art is static. It was not at all static, but it was one of the most important art schools in the world, which as time passes, it is more appreciated, and the Greek intellectuals who tell you that Byzantium did not create anything are blind.

So the ones that characterize Byzantine art as “simple imitation and copying” are probably mistaken.

If

you make something excellently, then you can repeat it excellently. But

there were always differences. Looking at an icon, we can assign a date

to it. If they were all the same this would not happen. There were

specific traditions that were maintained, but this art is very different

from century to century. It got 'stuck' and remained the same after the

fall of Turkish rule, because illuminated sponsors were missing from

your country.[2] The art of the Palaiologoi is very different from the

art of the Justinians. Certainly it was also analogous, but it was not

imitative. Things are simple: the people who persecute Byzantium never studied it, and started out with prejudices against it. They do not know what it achieved, what it accomplished.

Greece, Byzantium, modern Democracy

Some

claim that Byzantium was not Greek and was not a continuation of

ancient Greece. There was no democracy, or even democratic institutions.

I don't believe that contemporary Greeks are more Greek than the Byzantines. In

time, in the course of centuries, races do not remain pure, but certain

characteristics of culture remain ethnic. The Byzantines used the Greek

language―that has changed a little, but languages change. They were

very interested in philosophy and the philosophical life. They may have

been subjugated to an emperor, but this emperor had to behave correctly,

because uprisings among the people took place easily. The worse that

one could say about Byzantium was that it was a bureaucratic state. But it had a very educated bureaucracy, much more educated than the bureaucrats in today's world.

And,

what do you mean when you say the word “democracy”? Was all of ancient

Greece democratic? No. I would say to the Greeks who claim such a thing,

to read their own history, especially that of classical Greece. There

they will find a lot to judge... I never understood exactly what

“democracy” meant. In most places of the world today, democracy means to be governed by mass media, newspapers and television. Because it is desirable to attain what we call “people's vote” but, from

the minute that people cannot judge on their own―and there are many

people in the modern world that do not think―then they transfer this

authority to the hands of the Media, who, with the power they

have, should choose the difficult path and educate all whole world.

Many, not all fortunately, are irresponsible. Democracy can exist only

if there is a highly educated public. In a city like ancient Athens,

there was democracy―without considering how slaves and women went

through―because the men were very well educated. Usually they did not

elect their governors, they drew lots, as if they were leaving it in

God's hands―nothing like the House of Commons.

Was there a social state in Byzantium?

Was there a social state in Byzantium?

The

Church did a lot for the people. Byzantium had utter social

understanding. The hospitals were very good, as well as the nursing

homes, which mainly belonged to the Church, but not only to it; there

were also public ones. Let us not forget that one of the most senior

officials was the head of orphanages. Surely, the

Church played a key social role. It was not only about a regime of

hermits sitting on Mount Athos. There was also that, but there was a

system of monasteries in the cities. The monasteries looked after the

homes for the elderly, and the monks educated the youth―especially boys,

as girls were educated at home―and most provided a very good education.

Girls in Byzantium often received a better education, because they “enjoyed” more private attention. I think the marks we would give to the social work of the Church in Byzantium would be particularly high.

And their education, according to Basil the Great, had to be based on Homer, the “teacher of virtues”. They

were experts of ancient Greek Writings. It is worth mentioning,

nevertheless, that they did not pay particular attention to the Attic

Tragedians, but to the rest of the poets. There is the famous story of

an attractive lady, a friend of an emperor, that Anna Komnene narrates

to us. As the lady was passing by, someone yelled a homeric phrase to

her, referring to Helen of Troy, and she understood the innuendo. Nobody

needed to explain to her, whose lyrics they were. All boys and

girls without exception knew Homer. Anna Komnene never explains the

points referring to Homer, all her readers were familiar with

them.

Were there no uneducated people in Byzantium?

The

problems of Byzantine writing were different. They were so

knowledgeable of ancient Greek writings that they were influenced in

their linguistic formation. Many historians wished to write like

Thucydides; they did not want to write in the language that was more

natural to them but in the ancient. The great tragedy of Byzantine

writings was their dependence on classical writings. Not because they

did not have enough knowledge, but because they had more knowledge than

necessary, for their own “creative” well-being.

Would you like to live in Byzantium?

I

don't know personally if I would be suited for the Byzantine period. If

I lived at the time, I think, I would find comfort in some monastery,

living, like many monks lived, an intellectual's life, buried in the

wonderful libraries they possessed. I don't think I would want a life in

Byzantine politics, but it is very hard to find a period in world

history in which you would like to live... It all depends on the

government, the society, the class in which you are born. I would like

to live in 18th century Britain, if I was born an aristocrat. Otherwise,

I wouldn't like it at all. It's very difficult to answer your

question. ...

Orthodoxy.

How do you view Orthodoxy within this circle?

How do you view Orthodoxy within this circle?

I

have a deep respect for Christian dogmas, and especially for Orthodoxy,

because only Orthodoxy recognizes that religion is a mystery. The Roman

Catholics and Protestants want to explain everything. It is pointless

to believe in a religion, believing that this religion will help you

understand everything. The point of religion is exactly to help us

understand the fact that we cannot explain everything. I think that

Orthodoxy retains this valuable feeling of mystery.

But do we need mystery?

We need it. We need the knowledge that implies that in the universe there is much more than what we can understand. We need intellectual humility, and this is missing, especially among Western ecclesiastical men.

This is a characteristic of Orthodoxy and their Saints―the respect for humility.

How do you comment on the fact that many Saints got involved in politics and practiced political?

All who wish to influence people use politics and are politicians. Politics means trying to organize the 'Polis' (city) in a new way of thinking. The Saints are politicians. I never believed that you could separate the faith toawrds the Saints from intellect. I return to what I said about the Churches. From the minute you try to explain everything, you essentially destroy what should constitute human insight, which connects intellect to Saints and the sense of God.

All who wish to influence people use politics and are politicians. Politics means trying to organize the 'Polis' (city) in a new way of thinking. The Saints are politicians. I never believed that you could separate the faith toawrds the Saints from intellect. I return to what I said about the Churches. From the minute you try to explain everything, you essentially destroy what should constitute human insight, which connects intellect to Saints and the sense of God.

Intellect, politics, and faith in the Divine: So, can they march together?

Your

town, Thessaloniki, is an example. It was very famous for its

intellectuals, especially in the later Byzantine years. But it also had

help from its military, as Saint Demetrios, were coming to rescue her on

the right moment. Faith in Saints gives you courage to defend the city

from attacks, as Saint Demetrios did.

How do you view the other churches?

The

Roman Catholic Church was always a political institution, apart from

being a religious one, and was always interested in the law. We need to

remember that when the Roman Empire collapsed in the West, and the

barbaric kingdoms arrived, the Roman rulers were lost, but the church

officials remained, and they were the only ones with a Roman education.

So they were used by the barbarian leaders to impose the law. In this

way, the Western Church was “muddled up” with law. You can see the law

in the Roman Catholic Church; it wants to legally secure everything. In

Byzantium―and it is interesting how even after the Turkish conquest the

substructures remain―the Church is interested only in the Canon, the law

of the Scriptures. It does not desire to determine everything. In the

Western Churches that broke away from the Roman Catholic Church, the

need of law, of absolute specifications, has been inherited. It is very

interesting for one to study―and I have been studying for some time―the

dialogue between the Anglican Church of the seventeenth century and the

Orthodox. The Anglicans were rather unsettled because they could not

understand what the Orthodox believed regarding the turning of wine and

bread into body and blood. The Orthodox said “it is a mystery which we

cannot comprehend. We believe it happens, but how we do not know”. The

Anglicans, like the Roman Catholics, wanted a clear answer. This is the

typical difference of the Churches, and that is why I love the

Orthodox.

What do you think about modern Greeks?

This

quick understanding of things and situations is still alive among the

people. There is also a strong presence of the other quality of the

Byzantines: lively curiosity. And modern Greeks retain, like the

Byzantines, perception of their importance in the history of

civilization. All this indicates historical unity. Besides no race can

retain all its characteristics untouched. A lot depends on the language,

which is the best way to retain tradition. The writers of Byzantium

were hurt from their relationship to the ancient writers. Fortunately,

the modern Greeks have modern Greek that has allowed modern Greek

writers to advance, to progress in a way that the Byzantines did not

manage, excluding Cretan literature and Digenes. The great Byzantine

masterpieces were most probably folkloristic.

A Walk in the Garden and Poetic Stories[3]

I

first met Seferis when I was in Greece, right after the war. When he

came as an ambassador to London, I used to see him often. During that

time, I passed a lot of my time on an island of the west coast of

Scotland, with its mild climate because of the Gulf Stream. An alley of

palm trees lead to my house. He came and stayed over together with his

wife. The weather was wonderful as it often is there, and he said to me

“It is even more beautiful than the Greek islands”―very polite on his

behalf. We corresponded by mail regularly up until his death... when he

left London, for Athens, he left me his cellar, a cellar containing

exclusively ouzo and retsina. I still have not drunk all that ouzo, I

have... he had said that “the Celts are the Romioi of the North”, yes,

he enjoyed making such remarks. However, here he is quite right...

Kavafis

is one of the greatest poets of the world, and indeed original... I

cannot read Kazanzakis, I knew him personally, but I cannot read him, I

never liked him to be honest. I like Elitis and once in while I find

something special in Sikelianos. I don't know the younger ones; I

stopped following, as you know I belong to a very old generation.

FOOTNOTES

[1]Trans.

Note: Often also referred to as “Romiosini”. Some also explain the word

as referring to the Greek Roman Empire of the East. However, as Prof.

Clifton Fox says: “The people of the 'Byzantine Empire' had no idea that

they were Byzantine. They regarded themselves as the authentic

continuators of the Roman world: the Romans living in Romania.” It is a

word still used by some Greeks and, though it has no set definition, it

is usually used for those Greeks who adhere to the Orthodox Christian

faith and a certain ideal and spirit connected to the Byzantine Empire.

(See:

http://www.romanity.org/htm/fox.01.en.what_if_anything_is_a_byzantine.01.htm)[2]the Byzantine iconographers are not known to us because the maker of the church was considered the sponsor, the one who granted the money and of course retained an opinion on the total outcome. In very few instances we know the name of the iconographer or architect, in the nine centuries of Byzantium, but almost always the name of the sponsor is known to us.

[3]Sir Steven guided us around the garden of his home, after the interview, talking freely, about his beloved greek friends. The conversation was almost all of it “off the record”, except from the extracts being published here, which in his knowledge were told “on camera”, as he was showing us the most ancient tree in his garden.

source

No comments:

Post a Comment