In an exclusive excerpt from his new book 'Ten Popes Who Shook

the World,' one of the world’s most highly regarded historians of

Christianity discusses the historic power of the papacy.

The papacy is an institution that matters, whether or not one is a

religious believer. The succession of the popes, all 262 of them, is the

world’s most ancient dynasty. The Roman Empire was young when the popes

first emerged onto the stage of history, and the earliest references to

them, in the late second century, already claim for the bishop of Rome a

status greater than that of any other Christian leader. Eighteen

centuries on, the popes exercise a quasi-monarchic rule over the world’s

largest religious organisation. They touch the consciences, or at any

rate the opinions, of almost a fifth of the human race. The papacy has

endured and flourished under emperors, kings and robber barons, under

republican senates and colonial occupations, in confrontation or

collaboration with demagogues and democrats. And by hook or by crook, it

has survived them all.

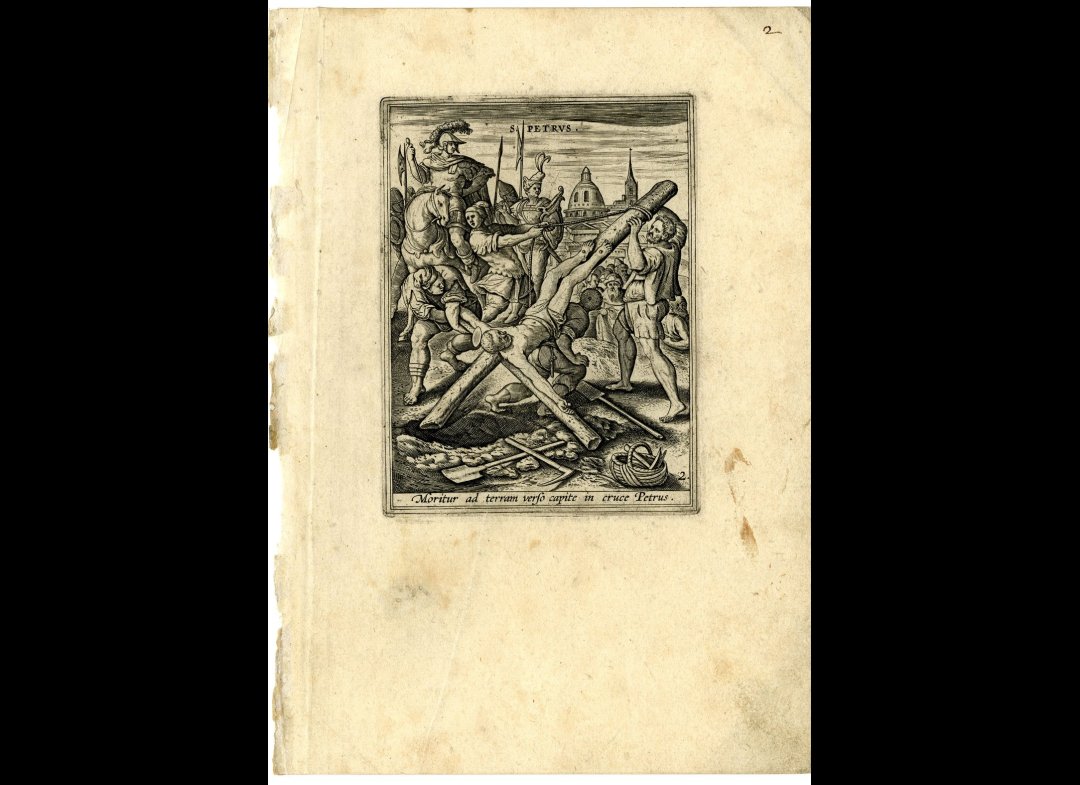

The popes themselves have never been in doubt about the coherence of

papal history, or its source. From the beginning they have claimed

divine warrant for their office as an institution established by Christ

himself, destined to endure as long as the human race. In the key papal

text from St. Matthew’s Gospel, the papacy (in the person of St. Peter)

is described as the rock on which the Church is founded, "and the gates

of hell shall not prevail against it." (Read on after the slideshow for more from "Ten Popes Who Shook the World.")

For non-Catholics, of course, the significance of the papacy stems

not from its religious claims but from its impact on human affairs.

Thomas Hobbes famously remarked that the papacy was "not other than the

ghost of the deceased Roman Empire, sitting crowned on the grave

thereof." The comment was certainly not intended as a compliment, but it

encapsulated an important historical reality nonetheless. Through no

particular initiative of their own, the popes inherited the mantle of

Empire in the West; the papacy became the conduit of Roman imperial

values and symbolism into the European Middle Ages. In a time of

profound historical instability at the end of antiquity and in the early

Middle Ages, the see of Peter was a link to all that seemed most

desirable in the ancient world, custodian of both its sacred and its

secular values. The papacy embodied immemorial continuity and offered

divine sanction for law and legitimacy. So popes crowned kings and

emperors and, on occasion, attempted to depose them. Even in the eighth

and ninth centuries papal authority stood high, although the papacy was

the prisoner of local Roman politics and many of the popes themselves

were the often unlearned younger sons of feuding local dynasties.

The papacy stood outside the local entanglements of churches which

were embedded in the social, political and economic structures of their

societies. Submission and fealty to the papal "plenitude of power"

offered great landed institutions like monasteries exemption from the

more burdensome and immediate interference (and financial claims) of

local bishops. The adjudication of the popes in the countless

jurisdictional, doctrinal and disciplinary disputes of Christendom was a

resource appealed to by all parties. Had papal authority not existed in

the Middle Ages, it would have to have been invented.

Papal claims reached their height in the central Middle Ages, and

were often turned by the popes into a platform from which to dominate

the world. This tendency was already evident in the career of the great

and forceful ninth-century pope, Nicholas I, who confronted and faced

down emperors. It reached its most famous expression in the early 14th

century with Boniface VIII, whose bull Unam sanctam declared

that it was "altogether necessary to salvation for every human creature

to be subject to the Roman Pontiff." Everything the modern papacy

claims, and very much more besides, such as the papal deposing power,

was claimed for the popes then.

In

the high Middle Ages the popes most certainly shook the world. It was

an 11th-century pope who first called on the armed force of Christendom

to "liberate" the great pilgrimage sites of Jerusalem and the Holy Land

from Muslim domination: the crusades were the result, inaugurating a

centuries-long bloody episode whose consequences reverberate still.

In the centuries after this zenith of papal influence, the papacy

went on insisting on the universality of its spiritual authority, but in

reality it declined drastically, even among all the Catholic powers of

Europe. The Renaissance popes could command the greatest artists and

architects in Europe, and they created a Christian Rome whose glories

were designed to outshine pagan antiquity, and to assert the claims of

the papacy against dissent within and beyond the Catholic Church. But

the spiritual claims of the papacy were complicated and, in the eyes of

many, compromised by the fact that the popes all too often behaved like

mere Italian princes, aggrandising their relatives (including their

children) while exerting over the Church a hold which had as much

dynasty as divinity about it. The rock on which the Renaissance popes

founded their fortunes was not so much Christ’s promises to Peter, as

the papal monopoly on the mining of alum, the rare mineral essential for

the tanning of leather.

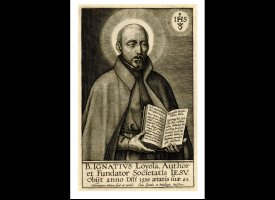

Large tracts of northern Europe repudiated papal authority during the

Reformation of the 16th century. But the papacy, which even to Catholic

reformers had seemed almost hopelessly corrupt, made a startling

recovery. As Catholic institutions and Catholic doctrine came under

threat, the popes emerged as a centre of continuity and a spearhead of

renewal. Rome became both the executive centre and the symbolic focus of

a resurgent and aggressive Catholic Counter-Reformation. But

paradoxically, this very resurgence of papal energy triggered a reaction

among the Catholic powers of Europe. They began to find irksome the

ancient claims of the popes to intervene in secular matters. Popes of

the time might have inhabited buildings that spelled out an almost

megalomaniac vision of papal dominance, like the monstrous bronze

baldachin that Pope Urban VIII raised over the papal altar in St.

Peter’s, embossed with enormous heraldic bees from his own family’s coat

of arms, but in reality the popes were in serious danger of being

reduced to purely ceremonial significance. In 1606 Pope Paul V put the

entire Venetian Republic under solemn interdict for what he saw as

incursions on papal authority. Interdict was the popes’ most formidable

weapon, a collective excommunication and ban that in theory halted the

celebration of any sacraments and rites -– Baptism, the Eucharist,

Marriage, Christian burial -– throughout Venetian territory. But the

rulers of Venice called the Pope’s bluff, forcing the clergy to carry on

as usual or be banished. After a year of deadlock, the Pope was forced

into a humiliating climbdown. Underneath the elaborate deference of the

Catholic world, the papacy and its often inconvenient religious demands

were resisted. Cardinal Richelieu said of the Pope, "We must kiss his

feet -– and bind his hands." So the kings and queens of Catholic Europe

appointed their own bishops, taxed the clergy, policed contacts between

the local churches and Rome, restricted the publication of papal

documents, determined the syllabus in the seminaries and expelled or

dissolved the religious orders as they pleased. And in all this the

popes grumbled, protested and complied.

The modern papacy, therefore, with its unchallenged jurisdiction over

the whole Catholic Church, is not the product of a steady evolution

from simple beginnings, the natural growth of some essential acorn into a

mighty oak. In a real sense it is, rather, the result of a historical

catastrophe, the French Revolution. The Revolution swept away the

Catholic kings who had appointed bishops and ruled churches, and once

more made the popes seem the embodiment of ancient certainties. The

hostile secular states that emerged in 19th-century Europe attempted to

reduce the influence of the Church in public life, but they were happy

to leave its internal arrangements to the Pope.

The most crucial and important practical power possessed by modern

popes is arguably the right to appoint the bishops of the world, and

thereby to shape the character of the local churches. It is salutary to

remind ourselves that the popes did not possess this unchecked power in

canon law until 1917, and the practice of direct papal appointment of

bishops did not become general until the 19th century. Before then the

Pope’s role in appointing bishops was not generally as universal pastor

but as Primate of Italy or as secular ruler of the Papal States. The

1917 Code of Canon Law itself, which lies at the heart of papal

domination of the modern Church, arguably owes at least as much to the

Napoleonic Code as to Holy Scripture, and the exercise of papal

authority in the modern Church is rooted in quite specific aspects of

the institutional and intellectual history of the last 200 years.

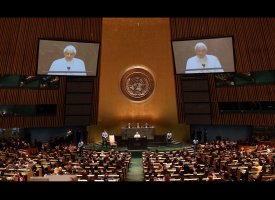

Whatever its roots and its vicissitudes, papal influence over world

events remains formidable. Popes no longer mobilise armies or launch

crusades, but over the last century or so a greatly enlarged papal

diplomatic corps of nuncios and apostolic delegates has secured for the

modern popes powerful representation to most of the governments of the

world, and in international bodies like the United Nations. Catholics

form a fifth of the world’s population, and the Catholic Church is the

world’s largest conglomerate of humanitarian and relief organisations.

Those facts alone give immense significance to the opinions and actions

of popes.

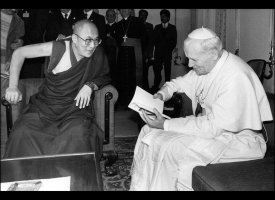

It was because they knew that the words of the Pope had the power to

move millions that the Allies in the Second World War were so determined

that Pope Pius XII should condemn Nazi atrocities. And with the rise of

instantaneous modern communications and modern forms of travel, the

popes have gained a direct and imaginative presence in both Church and

world unthinkable in earlier ages. The capacity to translate that

symbolic religious valency into world-shaking action was startlingly

demonstrated by the crucial role of Pope John Paul II in the fall of

communism in Poland and the wider Soviet bloc. For good or ill, the

popes continue to shake the world.

Adapted from 'Ten Popes Who Shook The World' by Eamon Duffy,

published by Yale University Press in November 2011. Reproduced by

permission.

Eamon Duffy is professor of the history of Christianity,

Cambridge University, and fellow and former president of Magdalene

College. He is the author of many prizewinning books, among them 'Fires

of Faith,' 'Marking the Hours' and 'Saints and Sinners.'

No comments:

Post a Comment