Near the Syrian city of Aleppo, the Church of St. Simeon

the Stylite commemorates the 5th-century ascetic who

became an ancient sensation by living atop a tall pedestal

for decades to demonstrate his faith. Krak des Chevaliers,

an awe-inspiring castle near Homs, was a fortress for the

order of the Knights Hospitaller in their quest to defend

a crusader kingdom. Seydnaya, a towering monastery in a

town of the same name, was probably built in the time of

Justinian.

|

| The Church of St. Simeon the Stylite commemorates the 5th-century ascetic. Photo: Getty Images. |

A

nun there spoke about Syria's current crisis from

within a candlelit alcove this week, surrounded by

thousand-year-old votive icons donated by Russian

Orthodox churchgoers and silver pendants in the shape

of body parts that supplicants have sought to

heal—feet, heads, legs, arms, even a pair of

lungs and a kidney.

"It's not a small thing we are facing," she

said, speaking as much about the country as her faith.

"We just want the killing to stop."

Few places are as central as Syria to the long history of

Christianity. Saul of Tarsus made his conversion here,

reputedly on the Street Called Straight, which still

exists in Damascus. It was in these lands that he

conducted his first missions to attract non-Jews to the

nascent faith.

A century ago, the Levant supported a population that was

perhaps 20% Christian. Now it is closer to 5%. Syria today

hosts vibrant, if dwindling, communities of various

ancient sects: Syrian Orthodox, Syrian Catholics, Greek

Orthodox, Greek Catholics and Armenian Orthodox.

But Syria's Christian communities are being severely

tested by the uprising that has racked the country for

more than a year. They think back to 636, when the

Christian Byzantine emperor Heraclius saw his army

defeated by Muslim forces south of present-day Damascus.

"Peace be with you Syria. What a beautiful land you

will be for our enemies," he lamented before fleeing

north to Antioch. In the 8th century, a famed Damascus

church was razed to make way for the Umayyad

Mosque—today one of Islam's holiest sites.

Not a few Christians in modern-day Syria worry that the

current crisis could end the same way for them if Bashar

al-Assad and his regime are defeated by the rebel

insurgency.

In many ways, it is an odd concern. Christians and Muslims

have lived side-by-side with minimal friction during the

decades of Assad family rule. Historically, local

Christian communities have sometimes even welcomed Muslim

overlords when they freed them of heavy-handed rule from

Constantinople or Rome. In many places the two groups

continue to reach out to each other even now. Even rebel

extremists say that they don't have anything against

Christians, either.

Yet as the conflict inside the country takes on

ever-stronger sectarian overtones, as Christians largely

side with the regime or at least decline to actively

oppose it, some of the oldest Christian communities on

earth are feeling squeezed.

"We have been leading a life that has been the envy

of many," says Isadore Battikha, who until 2010

served as the archbishop of Homs, Hama and Yabroud for the

Melkite Greek Catholic church. "But today fear is a

reality."

Father Battikha is among the many staunch supporters of

President Assad in the Christian church hierarchy.

From the very start of the current conflict, history and

religion have played a key role in fueling passions on

both sides in Syria. And this has become more pronounced

as the conflict dragged on, turning bloodier and more

vicious.

One of the oft-repeated assertions made by the Syrian

regime plays effectively on ancient rivalries. The

conflict, it says, is an attempt by neo-Ottomans in Turkey

and expansion-minded Muslim ultraconservatives from Saudi

Arabia—known as Wahhabis—to gain a foothold in

Syria.

This narrative, one of majority Sunni Muslims overwhelming

and dominating minorities, is now a staple of nightly news

bulletins on Syrian state television. The regime knows

well how this message resonates with Christians and other

minorities.

The Ottomans, Turks who ruled Syria from 1516 until World

War I, relegated Christians to a second-class citizen

status. They were allowed to practice their religion and

govern themselves in matters that didn't concern the

Muslims. But they were also required to pay special taxes,

and there were plenty of restrictions on them when it came

to interactions with Muslims. Wahhabism, the ascetic and

harshly conservative form of Islam practiced in Saudi

Arabia, is even tougher on Christians.

Rebels have made it easy for the regime to play on fears

such as these. In an effort to inspire their own fighters

and curry favor with foreign backers—primarily Saudi

Arabia and Qatar, the only other country where Wahhabism

is the state religion—some frame the conflict as a

struggle to restore the glories of the Islamic caliphates

and redeem Syria from the rule of the infidels.

This clearly comes through in the names adopted for the

brigades of the Free Syrian Army—the loosely linked

grouping of local militias and army defectors. Many of the

militias are named after figures revered by Sunni Muslims

like the third Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab, whose main

title was al-Farouq, meaning "distinguisher between

truth and falsehood," and the Islamic warrior and

military commander Khalid ibn al-Walid.

It was Ibn al-Walid, fighting for the Caliph Umar, that

defeated Emperor Heraclius in 636 during the first wave of

Muslim conquest to come from the Arabian Peninsula in the

years after the death of the Prophet Muhammad.

The main target of the most sectarian-minded rebels isn't

Christians. It is the Alawites, the minority group to

which the Assad family belongs. Alawites, who make up

about 12% of Syria's population, about the same as

Christians, are a heterodox sect that branched off from

Islam. They are considered by Muslim extremists to be

heretical, far worse than Christians.

Nonetheless, many Christians fear any government that

replaces the Assad regime might be dominated by groups

like the Muslim Brotherhood that could relegate them back

to second-class status. They also worry their communities

could be devastated in the crossfire between Syria's

largely Sunni Muslim insurgency and the well-armed Alawite

regime, just as Christians in neighboring Iraq have

suffered mightily in the sectarian wars there over the

past decade.

The expansion of the conflict to Syria's two biggest

cities, Damascus and Aleppo, has amplified the fears of

the Christians. They are under pressure from both the

regime and rebels to take sides and make their allegiances

known. Those who want to avoid taking sides are leaving.

For the time being many Christians, like Muslims and other

refugees, have relocated to areas where they feel safer

within Syria or in neighboring Lebanon. So far, the

pattern in neighboring Iraq—where many Christians

have left for good to Western countries—hasn't

emerged.

The clearest examples of Christians taking the side of the

regime have been in Homs. In the town of Qusayr, southwest

of Homs, one Christian family helped aid the security

forces by taking up arms and manning checkpoints. The

result was a backlash against all Christians there, and

the town has largely emptied of Christians since then.

In Wadi al-Nasara—the Valley of Christians, another

enclave of some 30 villages west of the city of

Homs—a family of pro-regime Christians has fought

alongside Alawite loyalists, say residents who recently

fled the area. Pro-regime Christians commandeered two

palaces in the scenic valley that are owned by Gulf Arab

diplomats, they said.

Nearby, Sunni fighters have made a base in the landmark

12th-century Crusader-era castle Krak des Chevaliers.

"It is now impossible for a Muslim to come down to

the valley," said a resident of the area.

Father Paulo Dall'Oglio, an Italian Jesuit priest who

lived in Syria for three decades but was expelled by the

regime in June, says many members of the church have

long-standing ties with the regime and intelligence

services that have shaped their stance.

|

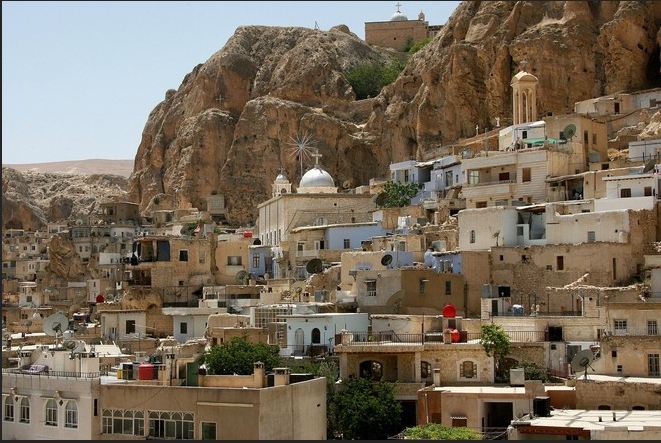

| A general view of the Christian Syrian village of Maalula, 60 kms north of Damascus. Maalula is one of the last corners in the world where its residents still speak Aramaic, the mother tongue of Jesus Christ. Photo: Getty Images. |

"Many

Christians in Syria believe that there's no alternative

to the Bashar Assad regime," says Father

Dall'Oglio.

Some Christians, though, are striving to bridge that

divide, attempting to reach out to the opposition and

rebels, or at least cross the sectarian gulf that

increasingly separates them.

Basilios Nassar, a Greek Orthodox priest from the central

city of Hama, was shot and killed by government snipers in

January while he was helping evacuate the wounded in

clashes in one neighborhood, Christian activists say.

They say the snipers probably mistook him for an Islamist

fighter because of his beard and black robes. His church

said he was killed by "an armed terrorist

group."

Caroline, a Christian activist who asked to be identified

by only her first name, was arrested by security forces in

April in Damascus while distributing chocolate Easter eggs

to the children of Christian, Sunni and Alawite families

displaced by the fighting in Homs.

Paper strips bearing passages from the Quran and the Bible

were attached to the eggs. Caroline said this act was part

of her attempts to chip away at the barriers now

separating Syria's religious groups because of the

conflict.

Previously she made it a point to assist the wives and

children of men killed in fighting in the predominantly

Sunni town of Douma outside Damascus, handing out food

provisions and cash envelopes.

She had also sought meetings with church leaders to ask

them "not to impose one position on all

Christians." She said the majority either scolded her

for being against the regime or refused to meet with her.

Father Nawras Sammour, a 44-year-old Jesuit from Aleppo,

runs a nationwide relief program known as Jesuit Refugee

Services. The group is currently providing assistance to

6,000 Syrian families across the country who are displaced

by the violence—Sunni and Shiite Muslims, Druze,

Alawite as well as Christian.

He believes only by reaching out across religious divides

will Christians continue to be a vibrant presence in these

ancient lands. He recognizes the challenges, and says he

understands Christian concerns.

"Look at Iraq, look at Egypt," he says, listing

neighboring countries where political upheaval and the

replacement of an authoritarian ruler with an Islamist

resurgence has pummeled long-standing Christian

communities. "But despite this we have to build

bridges. These are the principles of the gospel. We can't

just pick a side and go with them."

Alexander Haddad, a 66-year-old resident of the mountain

hamlet of Maalula, is concerned about the fate of his

ancient Christian community, but he takes the long view.

Like other residents of the town, he speaks a variant of

Aramaic, the language used by Jesus himself.

"A lot of people have passed through this

country—the Byzantines, the Muslims, Tamerlane, the

Mongols, the Ottomans," said Mr. Haddad, seated in

the shadow of the convent of St. Thekla, the feminine hero

of the biblical legend, the Acts of Paul and Thekla.

"Jesus was from just to the south. St. Paul came to

Maalula," he says. "Christianity is very strong

here."