The

first slanderer was the devil. The word

“devil” itself comes from the Greek word

meaning slanderer.

The Lord Jesus Christ said of him, When he speaketh

a lie, he speaketh of his own: for he is a liar, and

the father of it (Jn. 8:44). The God-Man, Jesus

Christ was once crucified, and his disciples were

treated in like manner as their Teacher, especially if

they preached their faith.

Out of all the twelve apostles, only St. John the

Theologian did not die a violent death. If we look at

history, we can see that almost all those who spread the

Gospels had to endure slander.

St. Philaret (Drozdov) notes: “The path of a

missionary is not an easy one.”

The wise hierarch gave his advice to the missionary to

the Altai, Archimandrite Macarius (Glukharev), that he

should view the missionary work he has taken up with

“a cautious eye. This is an evil age, it does not

readily trust pure goodness; it greedily snatches any

opportunity for complaint and slander. The sting of

mockery, even if it’s unfounded, can sometimes

wound and cause harm to the achievements of good

endeavors”

This advice was given in the early nineteenth century,

but we have to say that never was the degree of hatred

and slander so strong in Russian history as in the late

nineteenth, early twentieth centuries.

Up until 1905, thanks to the censors, it was very hard if

not impossible to slander openly. Therefore, authors took

the alternative route of writing literary works which

portrayed one or another missionary under the guise of

negative characters.

Thus, for example, the outstanding head of the Russian

Orthodox mission in Jerusalem Archimandrite Antonin

(Kapustin) was jeered at and vilified in the novelette,

Sidelocks Pasha and his consorts. Mosaics, cameos, and

miniatures from curious excavations in the slums of the

Holy Land”. This novelette was published in 1881

in St. Petersburg,and the author hid behind a pseudonym.

The reason for the appearance of the novelette, as

Archimandrite Cyprian (Kern) considers, was the struggle

between the Russian consuls in Jerusalem with the Russian

Orthodox Mission. “Taught by our synodal

organization to view the Church as something subject to

its authority, our bureaucrats dreamed of the

mission’s speedy liquidation along with its

indefatigable and independent head.”

Having exhausted all political efforts to remove the

absolutely irreproachable character of Fr. Antonin,

they turned to slander.

To the Archimandrite, who in the words of Professor

Dimitrievsky combed his hair in a way that made it look

like Jewish sidelocks and therefore could easily be

identified with the character Sidelocks Pasha, was

attributed such despicable and base deeds that they

lowered the entire novel to the level of a tabloid. But

unfortunately even that type of “literature”

has its readers. The novelette quickly circulated in both

Russia and the Holy Land. Although the government censors

finally pulled the book from the shelves, the dirty work

of slander had been accomplished—rumors were spread.

The slander did not affect the Synodal authorities’

relationship to Fr. Antonin. Although Archimandrite

Antonin outwardly viewed such “creativity”

with contempt, it must have had an unpleasant effect on

him. “The book brought disturbance into the quiet

and bright course of my life, and this has many times

surprised the people I have contact with,” he wrote

to V. H. Khitrovo on March 24, 1881. “The shameless

attacks on me from this human devil do not allow me to

completely be at peace. Until my death, I will feel like

answering that madman according to his

madness…”

As the contemporary researcher O. L. Tserpitskaya writes,

Fr. Antonin stopped leaving the mission without particular

official need. But people began to come to him for counsel

and consolation.

In Russia, interest in the Holy Land grew ever

stronger, and this was a consolation to the head of the

mission.

Toward the second half of the nineteenth century,

missionary efforts began to be aimed not only at the

spiritual enlightenment of non-Christian peoples as much

as it was at the enlightenment of the long-Orthodox

population of the Russian Empire, a movement which later

received the name, “internal mission”.

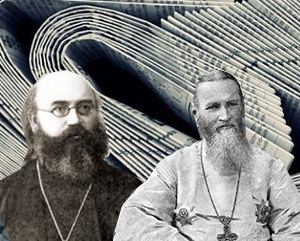

One of the most outstanding of these internal missionaries

of that time was St. John of Kronstadt. The majority of

his biographers write that during his studies he wanted to

become a missionary in Alaska, Africa, or China.,

but when he saw the loose life of the capital city, he

came to the conclusion that Russia “has enough of

its own pagans.”

Russia knew no few ascetics of piety at that time, but

there was no one more well-known than St. John of

Kronstadt. In the opinion of the famous Russian writer

Boris Shergin, this is precisely what led to cruel slander

against the righteous priest. Shergin wrote in his diary,

“They knew Fr. John of Kronstadt, but if the liberal

intelligentsia did not wish to notice Ambrose of Optina,

“they” slandered John of Kronstadt and slung

mud at him. Here the axiom, “The world lieth in

evil” (1 Jn. 5:19) is proven true. When it hears of

a saint, and if that saint is placed on a candlestand, our

generation not only does not lovingly appreciate or honor

him—they will take pains to trample his name into

the dirt.

The first noticeable composition aimed against the growing

acclaim of Fr. John was the short story by N. Leskov,

“The Midnighters”.

First published in the liberal magazine, Vestnik

Evropy, (“News of Europe”) at the end

of 1891, the story mocks the official Church and Fr.

John in particular, portraying him as cunning,

hypocritical, highly educated capital city priest,

contrasting him with the “saintly”

followers of Leo Tolstoy’s teachings.

It must be said that during that period N. Leskov

underwent a change in his views. According to Metropolitan

Anthony (Khrapovitsky), he had been drawn into the

sectarian “mysticism of Pashkov, and after a period

of desperate dabbling in spiritualism he joined in with

the views of Count Leo Tolstoy.”

To characterize the motives driving Leskov to write that

story, his correspondence with Count Leo Tolstoy is very

telling. In his letter of December 1890 he writes of Fr.

John, “His glory and the stupidity of society

continue to grow, just like the column beneath the

outhouse of a two story pub in a provincial town. In the

winter frost it even glitters, and no one knows what it

is—one can perceive it as something entirely other

than what it is. But it is a sure measure of

stupefaction.”

“I have gone and continue to go throughout my life,

but I love to check and fortify myself with your

judgments.” The letter is signed, “Your loving

Nicholas Leskov.” In another letter he writes,

“Forgive me for importuning you, and do not deprive

me of your moral support. Your dedicated Nicholas

Leskov.”

Leo Tolstoy likewise supported Leskov’s creative

development in that direction. For instance, he wrote

to Leskov, “Your story about J[ohn] is wonderful,

I laughed the whole time I read it out loud. What 900

years of Christianity has done to the Russian people is

terrible”

However, Leskov’s feelings for the Count were

entirely opposite. We see in the same letter:

Commenting on “The Midnighters”, Metropolitan

Anthony (Khrapovitsky), who had a deep respect for Fr.

John wrote: “In this story … there was a

resounding slap in the face of the Orthodox

Church…. One only has to open any sermon of this

pastor in order to understand how far from the truth these

accusations are of his lack of understanding of the

Christian Sacraments, and in part about new grace-filled

life, and rebirth…. The Orthodox pastor, of course,

has nothing to lose from Leskov’s slander; it would

be too strange if such a well-known figure were not

blackened by anyone, when it is written even of the Savior

Himself: Some said, He is a good man: others said, Nay

but He decieveth the people (Jn. 7:12).

Time has put everything in its place. The Tolstoy

societies have long ceased to exist, while Fr. John of

Kronstadt has been canonized a saint.

But at the time, after the manifesto of October 17, 1905

concerning freedom of speech, the attacks on Fr. John of

Kronstadt increased. In a play by V. P. Protopopov called,

“Black Ravens” created during the 1905

revolution, “The pastor was portrayed as a charlatan

healer, and his supporters as sectarians.”

The play was performed for the public in many theatres

of the empire in December 1907.

The clergy came to the defense of Fr. John. Bishop

Hermogenes (Dolganov; 1858–1918) of Saratov (who

would later become a martyr) did much to have this play

removed from the theaters.

On December 11, 1907, during an audience with Emperor

Nicholas II, the future hieromartyrs Hermogenes,

Seraphim (Ostroumov) and John Vostorgov related in

detail how the pastor was being harassed. “The

Tsar gave orders to Stolypin to remove the play from

the repertoire.”

For Fr. John Vostorgov who participated in the meeting,

Fr. John of Kronstadt was a living witness to the grace of

God that abides in the Church, a confirmation and

consolation to all Her children. “Here is the

manifestation of the power of the Lord,” exclaimed

Fr. John Vostorgov in one of his sermons (after someone

related how a seriously ill woman was healed by Fr. John

of Kronstadt’s prayers). “One of the many

miracles wrought in the presence of the wondrous faith,

meekness and piety of this pastor of all Russia. Have they

written about it in the newspapers?... We will ask all the

right newspapers to print this news. It is sinful to be

silent about the works of God.”

To characterize the spiritual and moral state of society

during the period just before the revolution, Fr.

John’s remarks from 1911 are very telling:

“One thoughtful observer said of modern Russian life

that it is ‘penetrated through and through with

hatred’. That is not a consoling characterization!

But if it is true with respect to political parties,

social strata and day-to-day groups of Russian society and

their interrelationships, then it is even truer with

respect to the feelings currently harbored against the

Church.”

Fr. John Vostorgov noted that on the pages of

“progressive” newspapers, every religion is

supported and respected. Only with regard to Orthodox

bishops, priests, and monks have unbelievably vile insults

and deliberately false accusations been allowed,

undermining any authority the Church may have.

Attacks against the Church from the revolutionary forces

in Russia were, in Fr. John’s words, “even

more vicious than those against the

autocracy.”

In Fr. John’s opinion, this was because it was

precisely the Orthodox Christianity living in

people’s souls that caused the revolution’s

failures.

“An onerous anxiety creeps into one’s heart at

the sight of this yawning abyss of hatred that is

surrounding the Church and those truly religious

people…. Seeing that the Church’s power has

decreased and no longer enjoys its former

“popularity”, the government, using the modern

vulgar expressions, readily refuses to protect the Church,

thinking to curry favor with progressive movements

and—a vain hope!—win them over to its side.

The secret enemy of the Church thus immediately succeeds

in achieving two goals: undermining the Church, and

undermining the government…. In society, amongst

the simple-hearted people who read the newspapers and

believe it all indiscriminately, mistrust and antagonism

toward the Church increase more and more with each passing

year. Among the faithful confusion, perplexity, and

complete misunderstanding grows, not knowing who or what

to believe. From year to year a mistrust of and alienation

from the Church is growing amongst the younger generation.

Especially amongst the simple people, the authority of the

Church is everywhere in decline, the ground is being

prepared for indifference, churchlessness, and the

acceptance of all sorts of sectarianism or even a

particular kind of “peasant nihilism”, which

with its manifestations and consequences is the most

terrible kind.”

It is an interesting thing, but slander has sometimes had

a “curative effect”. For example, slander in

the “progressive” and far right newspapers

about the pastoral courses in Moscow organized by Fr. John

Vostorgov provided the attendees of those courses an

opportunity to be “cured” of their trust of

the press. The papers wrote that the attendees had all

dispersed and that the courses were closed. Meanwhile, not

a single participant had left the course, and they

continued on without interruption.

As a missionary preacher in Moscow and mouthpiece of the

Church’s official position, the holy hieromartyr

John Vostorgov like no one else was subjected to all kinds

of slander and harassment. This was evoked by the fact

that Fr. John tried as hard as he could to guard his flock

from revolutionary ideas. That is why the revolutionaries

hated and persecuted him—he stood, in his own words,

“blocking their path”.

On the other hand, reasonableness and care for the

Church irritated the far right as well.

Harassment of the pastor had begun even during the period

of his service in the Caucasus. After being transferred to

Moscow in 1908, an entire volume of slander was published,

entitled “Archpriest J. I. Vostorgov and his

political activities”, compiled by N. N. Durnovo.

The book was widely distributed. It was given away for

free throughout Russia—it was handed out to all the

members of the State Council and State Duma, ministers,

and all major leaders, reprinted in all the left-wing

newspapers; and when Fr. John made his trip through

Siberia, he was met in every city by the

revolutionaries’ reprints of this lampoon.

The slander was so powerful that even quite sensible

people were perplexed when they met the man who had been

so viciously attacked. Thus, for example, in his memoirs

Metropolitan Evlogy (Giorgievsky) writes of his meeting

with Fr. John, “Archpriest John Vostorgov was a man

of outstanding intellect and great energy. There were many

rumors circulating about him during his lifetime, but

apparently they were unfounded.

To all the slander in force against him, Fr. John only

answered once, in his book, The Slander of N.

Durnovo. The answer of Archpriest Vostorgov,

which was published in 1909, and in which he

systematically, point by point, citing official documents,

revealed the falsity of Durnovo’s compilation.

Nevertheless, slanderous books continued to be

released.

Fr. John himself would say to his friends, “I often

have to walk over the yawning abyss of human hatred. It is

terrible to look into it, and it wrenches my heart with

pain and natural fear.”

Later, when Fr. John became a widower, the slander halted

the decision of the Holy Synod that had been proposed by

Metropolitan Macarius (Nevsky) of Moscow and Kolomna to

tonsure Fr. John a monk and consecrate him a bishop to the

vicariate of the Moscow diocese with the aim of uniting

all the missionary activity in the metropolia.

Some time later, after a fabricated sentence by the

Cheka, the holy hieromartyr John was executed on

September 5, 1918 in Khodinsky field.

In the modern world of information technology, society

continues to use particular methods of manipulating

information and special technology to control

people’s consciousness. Under such circumstances,

the destructive weapon of slander becomes even more

accessible and effective. This requires of us particular

caution with respect to various information, especially if

it is about people who are conducting vast religious

educational and missionary work.

These words of Patriarch Kirill sound extraordinarily

relevant in this regard: “Today the mass opinions of

people are determined not by God’s truth, but by

information technology… It is very important that

we, the inheritors of great Russia, who have gone through

the terrible trials of the twentieth century, would today

be capable of learning from the past and not repeat the

mistakes our fathers made on the eve of 1917.

No comments:

Post a Comment